Hello again, readers!

Previous research published in this blog has detailed a multitude of cyberthreats that regularly try to circumvent the cybersecurity principles and standards used to protect against them: malware families that try to break into a system for a wide variety of purposes, vulnerabilities that are exploited by a multitude of cyberattackers, sophisticated threat actors that distribute advanced persistent threats (APT), and all sorts of other challenges to global cybersecurity.

In this new post, we will be looking at a paradigm shift that has been detected in cybercrime throughout the year 2022: cybercrime-as-a-Service models. Cybercrime-as-a-Service models are not new and unique to the current year, but have been a growing trend for some time now, and since the beginning of 2022 in particular are changing the targets of cybercrime and thus the way it is conceived. This scenario entails new risks in cyberspace and, in some cases, puts cyber criminals one step ahead of cyber security incident response teams, as there is insufficient cyber security expertise to deal with this technique.

Traces of Cybercrime as a Service (CaaS) have been around since at least 2013, although the exact time at which these tactics began to be incorporated into cyberspace crime is unknown. Cybercrime as a service and its variants have probably originated as a consequence of the success over time of Software as a Service (SaaS) and Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), two legitimate and legal cloud-based computing models in which a provider provides necessary resources to its customers to operate in cyberspace in exchange for a pre-determined payment. In both cases, the provider provides whatever is necessary for the contracted service to work and the customer is responsible for using it. It is therefore a form of business in which at least two users or entities are involved. Email services could be a laconic example of Software as a Service (SaaS), where a provider develops and maintains the email platform and rents it to third parties to make use of it.

In line with the above, cybercrime-as-a-service is nothing more than an adaptation of the previous business model to the cybercrime domain: a threat actor with high technical skills and expertise develops and maintains a platform or solution that enables the execution of advanced and sophisticated cyberthreat campaigns and then rents it out to malicious third parties that could use it for their own benefit in exchange for a certain fee paid to the actor that developed it.

By incorporating the above technique into the field of cybercrime, the technical barrier preventing anyone from becoming a cybercriminal is broken, as any individual with a certain (by no means exorbitant) financial capacity could rent a cyberthreat and use it for his or her own cyberattack campaigns. This is one of the reasons why ransomware has become the biggest cyber threat facing medium-sized companies today, as Cybercrime as a Service has given rise to a multitude of variants that amplify this cybercriminal business model, among which Ransomware as a Service (RaaS) has become hegemonic over the last few years.

Ransomware as a Service (RaaS) could be considered a new monetisation method derived from the evolution and popularisation of ransomware whereby the actors who develop it, instead of trying to deploy the payload on a targeted system or network themselves, offer a rent to malicious third parties for the use of the malicious code designed in exchange for a specific payment and for a previously agreed period of time. In this way, the actors who develop the cyberthreat obtain a greater economic benefit, since they do not allocate their resources to a single cyberattack campaign that may or may not be successful, but will always obtain a profit from those cybercriminals who contract their services and, in addition, a possible extra profit in the event that each cyberattack is successful, given that different business options have been developed in this respect that amplify their capacity for profit. In addition, this model allows an actor to allocate its resources to the development, maintenance and improvement of the payload and the actors who have rented the service to launch a given cyber-attack without requiring high technical knowledge and skills.

Related to the above, cybercriminals involved in Ransomware as a Service activities use four specific monetisation methodologies: some threat actors advocate a monthly subscription to their ransomware services in the form of a flat fee, while others prefer to develop affiliate programmes whereby the initial actor earns revenue from the monthly subscription to their service and in addition a variable commission ranging between 20% and 30% of the total revenue received by the cybercriminal who had perpetrated a successful cyberattack and in which the affected organisation had paid the demanded ransom. In other cases, single-use licences are developed whereby a cyber attack can be launched for a fee, although this is not the most common business model. Some threat actors even demand a pure share of the profits without any upfront fee, although this model does not guarantee a fixed and lasting economic benefit, making it a potentially attractive methodology for threat actors that do not yet have a sufficient reputation or reputation in the cybercrime landscape.

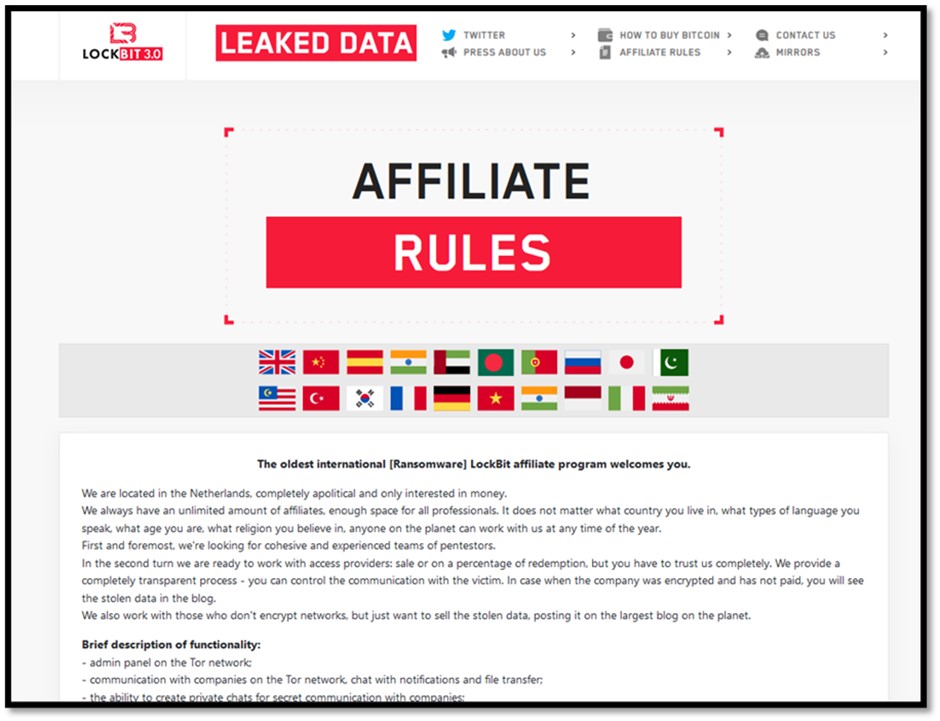

As an example, in the case of Lockbit, currently the main ransomware cyber threat, the actors responsible for its development and maintenance dedicate an exclusive section on their website to explain in detail the rules and methods of affiliation used in their Ransomware as a Service programme, which shows the sophistication of the cybercriminals who incorporate this business model into their criminal activity.

Ilustración 1 Rules on RaaS membership in Lockbit

In fact, Lockbit ransomware is one of the cyberthreats that proves that this cybercriminal business model is succeeding, as its high number of affiliates has made it the ransomware family with the largest number of victims and the highest risk at present. This explains why more and more ransomware actors advocate this monetisation technique.

On the other hand, it is worth noting that during the course of 2022 it has been observed that the business model that had been applied to ransomware has recently been adapted to phishing campaigns, which is novel, as sophisticated platforms of this type had hardly been detected until April when Frappo, a service initially conceived as a cryptocurrency wallet that ended up serving as a method of hosting phishing kits that allowed anyone willing to pay to impersonate reputable banks and organisations in the e-commerce, retail and online services sectors with a high sophistication level.

Ilustración 2 PhaaS Frappo Platform

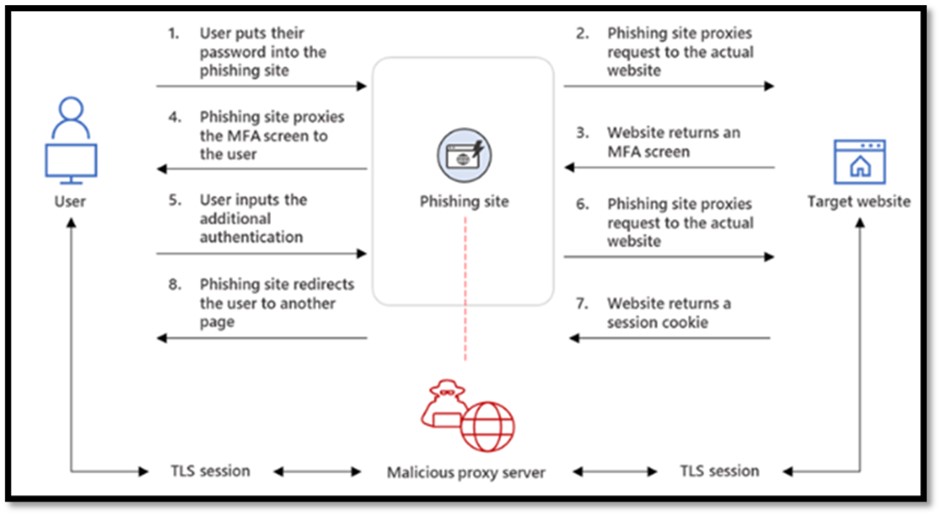

More recently, in May 2022, a new, more sophisticated Phishing as a Service (PhaaS) platform called EvilProxy, also known as Moloch, was announced, which could be a revelation in terms of phishing campaigns, as it incorporates advanced techniques historically associated with sophisticated threat actors such as reverse proxy and cookie injection, which significantly elevate the quality of phishing threats when used as methods of evading the second factor of authentication (2FA). These techniques have not been observed in the few previous Phishing as a Service campaigns reported to date.

Ilustración 3 Source: Resecurity. Available at: https://resecurity.com/blog/article/evilproxy-phishing-as-a-service-with-mfa-bypass-emerged-in-dark-web

Similar to Frappo, EvilProxy mostly targets the banking and e-commerce sectors, although publications posted by the threat actor that developed the service on specialised underground forums indicated that the platform has the ability to spoof organisations such as Apple, Facebook, GoDaddy, GitHub, Google, Dropbox, Instagram, Microsoft, Twitter, Yahoo and Yandex, among other entities and services. It is even suspected that this cyber threat could also target supply chain organisations, as it contains functionalities that allow phishing campaigns against Python Package Index (PyPi), the official software repository for third-party applications in the Python programming language, and JavaScript's Node Package Manager (npmjs), the package management system used in JavaScript's Node.js runtime environment. As an example, a potential attacker could direct EvilProxy's activity to the repositories of specialised staff, such as software developers and telecommunications engineers, with the purpose of also compromising the end users of those repositories when they try to install software that they consider legitimate because it comes from trusted resources.

Ilustración 4 Publication released by the actor EvilProxy announcing its PhaaS platform.

In view of the above, although Phishing as a Service is currently an incipient cyber threat, there is a possibility that it could lead to a golden age for this type of cybercrime, as has already happened with ransomware, because, if successful, it could potentially increase the number of cybercriminals executing this type of campaigns, while at the same time its quality increases thanks to the use of highly sophisticated phishing kits that can be constantly improved by the cybercriminals who develop these kinds of platforms.

There are also a variety of other cybercrime-as-a-service or business models that have gained prominence in recent years, such as Malware as a Service (MaaS), which could be considered the illegal equivalent of Software as a Service (SaaS), where threat actors promote the use of malware tools that can be rented by any user to execute large-scale cyber-attack campaigns of this type; Hacking as a Service (HaaS), where threat actors provide system exploitation services at very different levels (from account compromises and intrusions to carrying out denial-of-service attacks in any of their variants); or even Money Laundering as a Service (MLaaS), where money laundering services from cyber-attacks are provided through mules who receive the profits and execute transfers to hinder the subsequent investigation.

Therefore, to conclude this new blog post, reference should be made to a fact that stems from all of the above and that was introduced at the beginning of the research: the global cybercrime landscape is changing quickly. It is not only new types of cybercrime that are appearing, but also those that have been developing for years that are being enhanced and intensified. The current cyber threat landscape is evolving towards models that steadily increase their monetisation capacity and are therefore more lucrative for the actors promoting them. Thus, cyber-espionage, hacktivist or any other type of campaigns do not cease to take place, but they do take a back seat to the economic interest that increasingly often leads to the emergence of new groups of cybercriminals. This makes it possible to increase both the number and quality of for-profit cyberattacks that take place, as the various Cybercrime as a Service (CaaS) models allow for an increase in the number of cybercriminals executing them, as they do not require high technical skills and knowledge to design large-scale, low-cost cyberattack campaigns, while the actors that do have such capabilities can focus their resources on improving their service. However, it is not only the potential for monetisation that makes the adoption of these business models attractive to the cybercriminal sphere, but also makes it difficult to attribute each campaign to a specific threat actor, as the actor developing the campaign will not necessarily or probably execute the cyberattack, instead one of its affiliates will do this, thus complicating the cybercriminal network and the possibility of neutralising it.